Estimated Reading Time: 5 minutes

Recently, while attending a conference in DC, I was part of a discussion around the new NIST Digital Identity Guidelines (SP 800-63) and how “…it turned the password world upside down”. Soon we were discussing the studies that were cited, and the logic behind the new recommendations, and how this would help CISO’s “look like they are modern and adaptive”.

Specifically, there was a lot of excitement around one particular ‘requirement’. Section 5.1.1.2 of 800-63B states:

“Verifiers SHOULD NOT require memorized secrets to be changed arbitrarily (e.g., periodically). However, verifiers SHALL force a change if there is evidence of compromise of the authenticator.”

Based on various discussions and my LinkedIn feed, many have taken this to mean they could go back into the office, make an announcement about no longer mandating regular password changes, and get their 15 minutes of praise.

I’m sorry – but … seriously?

Before we get on with this little diatribe, let’s be clear – for as long as I can remember, I have been an ardent supporter of developing my security programs around the NIST doctrine. Hell – I am still a very proud owner of a printed copy of the entire Rainbow Series, which was about all that existed when I started in the industry. I guess that’s why I’ve been so troubled with the recommendations that came out of the new directive and, maybe even more so, the bandwagon jumpers that soon followed.

Over the past few months, I have read several studies which have analyzed ‘historical’ passwords of users and have found patterns of repetition and statistical similarity in the passwords people choose. While a simple evaluation of my own password methodology would support those findings to a degree, I struggling to understand why the radical shift in doctrine. Yes, the studies provide valuable, albeit a bit dated, information about the user psychology around passwords. While valuable information for anyone in our industry, when I look at the reality of the world we live in, I can’t help but wonder why the urgency of such a drastic change.

Now, I readily acknowledge that, at the end of the day, I am just a practitioner who deals with the ins and outs of protecting a corporate infrastructure every day. I do not pretend to be the think-tank types that performed these studies or those who developed the new standards. That said, from my perspective, I see two fundamental challenges with the proposed ‘No Arbitrary Change’ recommendation.

The Password Problem

First, lets be completely honest with each other. Password reuse happens. If you think otherwise, you’re either naive or delusional – pick whichever fits. A study by LastPass(4) shows that 59% of people use the same password for work and personal accounts – and get this – 55% of those people wouldn’t change their password if it was breached. Not only does password reuse happen with general users, but a recent survey by LastLine(1) shows that 45% of InfoSec professionals reuse passwords, which to me sounds extremely low given the reality of how many accounts we generally have. Additionally, a SailPoint survey(2) from earlier this year shows that 56% of IT decision makers reuse passwords. Considering these recent studies, if those in the industry admit to reusing passwords, how many of those who are not in the InfoSec community do you think do as well?

Now, when we relate these sobering statistics to the NIST requirement, how does it play? Not very well in my humble opinion. If you’d like proof, just ask yourself a very simple question – how many times has an end user reported a breach on their personal accounts to the corporate information security teams? My guess is your answer is someplace between close-to-never and ain’t-ever-happened.

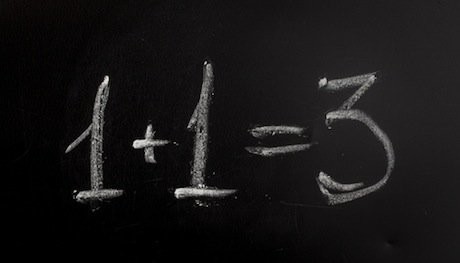

So, in my world, presuming that personal/corporate password reuse happens, and taking into account all of the personal breaches that have occurred over the last few years and gone unreported to the InfoSec team, I ask you, how does forcing a regular password change increase your risk as asserted by NIST? Because the user might use a password that’s already compromised? Or perhaps they will use one that’s statistically similar? Sorry, but I don’t see those possibilities being such a substantial risk that I’m turning off password aging.

Secondly, let’s think about exactly what we’re trying to protect against. If we’re trying to protect against a brute-force attack, then the appropriate lockout controls are likely already in place, not to mention that most security monitoring solutions are configured to alert the team well before the limit is reached (i.e. proactive monitoring would alert at 5 invalid attempts or less, if the lockout at 10). Its arguable that any enterprise that’s advanced enough to turn off password aging has such monitoring processes in place, so the overall threat is relatively minor anyway. The bigger question is how many organizations are at that level of security maturity.

If the concern is password cracking, then I think we have a far bigger issue than forcing a password change every 90 days. By definition, password cracking requires the capture of the encrypted password or hash, either off the wire or getting the entire user list from a directory. Either way, the protected information must be acquired, ex-filtrated, and processed. Let’s be frank – if this is the case in your environment, it’s already game over.

If we truly want to talk about the threats to identities in the enterprise, let’s talk about everyone’s favorite topic – SPAM & Malware. In most cases, we can count the minutes, if not seconds, between the receipt of a malicious email and the clicking of the link or opening of the document. Not weeks, or days, or even hours. A well crafted malicious email will have a user clicking on the link in most cases before any of the monitoring alerts have been seen, resulting in the user ‘logging into’ the fake site, supplying the attacker with everything they need to impersonate that user immediately. While we may be able to force that user to change their password at that point, what happens if that email went to their personal account? Considering the level of password reuse we (should) know we have, we now have a compromised account that no one knows about – a risk that would be somewhat mitigated by a password aging practice.

Taking these two perspectives into account, I find the NIST recommendation is entirely too myopic and fails to recognize the reality of what we do. While the recommendation may work for an extremely small number of advanced organizations who have the teams, processes and technologies in-place to remove password aging, what about those who do not? Most companies, especially those without security leadership(5), will simply remove the requirement without analysis, without protective measures in place, and without and understanding of the potential impact – and they would do it thinking it made them safer because NIST said so!

So, for the first time in my career, I find myself at odds with a trusted practice of leveraging NIST for my program. The reality however, is that I am the one who has to look my executives, my auditors and my users in the eyes every day and know I’m doing what’s best to protect them.

To that I say, sadly, Sorry NIST – not this time.

- NIST 800-63-3: https://pages.nist.gov/800-63-3/sp800-63b.html

- LastLine Survey: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/practice-what-you-preach-45-of-infosec-professionals-reuse-passwords-across-multiple-accounts-lastline-research-says-300682190.html

- SailPoint Survey: https://www.sailpoint.com/blog/world-password-day-2018/

- LastPass : The psychology of Passwords: https://www.techrepublic.com/article/report-only-55-of-users-would-change-password-if-they-were-hacked/

- Gartner 2018 CIO Agenda Survey: https://www.gartner.com/newsroom/id/3882863

For more on Identity and Access Management, view these articles.

Copyright © 2002-2025 John Masserini. All rights reserved.